We provide evaluation for head shape asymmetry, called plagiocephaly, for children from ages 2-3 months and up to approximately 12 months, however earlier evaluation is best. All cranial asymmetry must be investigated early to rule out serious causative factors.

Evaluations require a referral, and cranial measurements are provided to the Parents/Guardians and PCP (Primary Care Provider). We follow American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines, and are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Below are frequently asked questions about plagiocephaly, contact our office for questions or for additional information.

What is plagiocephaly?

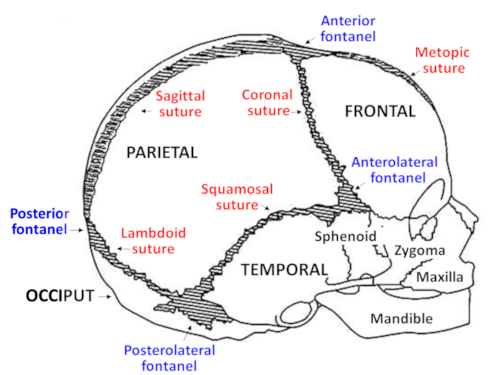

Plagiocephaly (play-gee-o-SEH-faly), a very common condition in infants, refers to an asymmetric head shape due to the misalignment or flattening of skull bones; it may involve asymmetry of the head or facial bones, or disproportion of the skull.

All infants are at risk for plagiocephaly because their skull bones are soft and malleable, and designed to move to allow for brain growth.

This is why AAP recommends screening for plagiocephaly starting at birth and at each well-child visit.

AAP also recommends “conservative treatment” to help improve or avoid plagiocephaly if possible, which includes positioning, exercise, and tummy time.

Children with tight neck muscles or torticollis have higher risk for plagiocephaly, so physical therapy may be added as part of conservative treatment.

Although most cases resolve within a few weeks or months, sometimes plagiocephaly is resistant to conservative treatment due to other risk factors.

What does it look like?

Plagiocephaly is usually noted visually, however head shape asymmetry can be difficult to see; it may be noted at birth, after several weeks or even several months.

Parents may first notice a “flat spot” on the back of the head, or one side; or the head may appear very wide, or very narrow.

Because plagiocephaly can affect facial bones, Parents may notice that one eye appears larger than the other, or that one cheek appears more prominent.

When looking down from the top of the head, they may see the ears are not aligned, or that one side of the forehead is more prominent.

The infant may have a preference to always sleep on one side; or they may have tight neck muscles on one side.

Plagiocephaly may first be seen in a photograph; or a PCP, therapist or family member may be the first to note it.

Cranial measurements can determine the severity of plagiocephaly. Our evaluation is provided to the Parents and PCP, and includes assessment of cranial proportion and alignment using the Orthomerica Starscanner Laser Data Acquisition System.

There is a time limit to address plagiocephaly, earlier intervention is best, between ages 2-3 months and ages 6-7 months.

Infographic: Symmetry Quick Screen

Are there risk factors ?

The infant skull has many moving parts, and there are many possible reasons for uneven bone movement during cranial growth. Plagiocephaly is individualistic, and each child’s is different.

Risk factors may be intrinsic (congenital), or extrinsic (acquired); certain risk factors may be known, others may be unknown. More than one risk factor may be involved.

Often Parents tell us they feel guilt or blame about their child’s head shape, however there may be risk factors involved that are out of their control.

Parents may provide positioning, exercise and tummy time, but see little improvement in head shape. Plagiocephaly may be resistant to conservative treatment due to unknown risk factors.

Tight neck muscles, or torticollis, is very common in infants and increases the risk for plagiocephaly.

Lack of information about plagiocephaly is a risk factor, because many Parents are not aware of it.

Parents may have reported a ‘flat spot’ but received an inadequate and unhelpful response such as: ‘don’t worry’; ‘minor cosmetic concern’; ‘wait and see’; ‘they will grow out of it’; ‘the hair will cover it.’

Any cranial asymmetry must be evaluated to rule out serious causative risk factors.

Guidelines and Recommendations

Conservative Treatment: Positioning, tummy time, and exercise

Plagiocephaly is very common because infant skull bones are designed to move to allow for brain growth. AAP recommends positioning, tummy time, and exercise, to help improve or avoid skull bone flattening and strengthen neck muscles.

Below are some ideas; speak with your PCP, or find more ideas online. If you notice a flat spot on baby’s skull, continue positioning and notify your PCP.

- position baby supine (on their back) starting at birth or within a few hours

- rotate baby’s head side-to-side regularly while supine to avoid flattening on one side, until they are strong enough to do this on their own

- counterposition baby on alternate ends of the crib, to encourage them to turn their heads

- continue positioning up to age 1 year, even after baby self-positions

- follow Safe Sleep recommendations

- encourages babies to lift and turn their head, exercises and strengthens neck and back muscles

- tummy time includes any time baby is facing the floor, for example when carried face down in a football hold, or when lying facedown across your knees or lap

- dress in clothing that protect but allows freedom to move head, shoulders, arms, legs

- avoid clothing, blankets and swaddles that restrict movement

- avoid prolonged immobility, and devices that restrict head movement in carriers, seats, cribs

- alternate right and left sides for feeding and holding

- provide a firm mattress, which allows baby leverage to push and roll; avoid spongy bassinet and playpen mattresses

- during playtime, alternate between supine and prone (on tummy) positions

- alternate sides for placement of toys to encourage turning and reaching movement

- provide playtime on a firm surface (play mat, rug) that baby can push against

- alternate placement of toys to encourage reaching and turning

Safe Sleep recommendations

Safe Sleep guidelines have reduced the incidence of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome); however, the incidence of plagiocephaly has increased. AAP recommends that parents follow recommendations for safe positioning, safe sleep environment, and safe maternal/infant health practices.

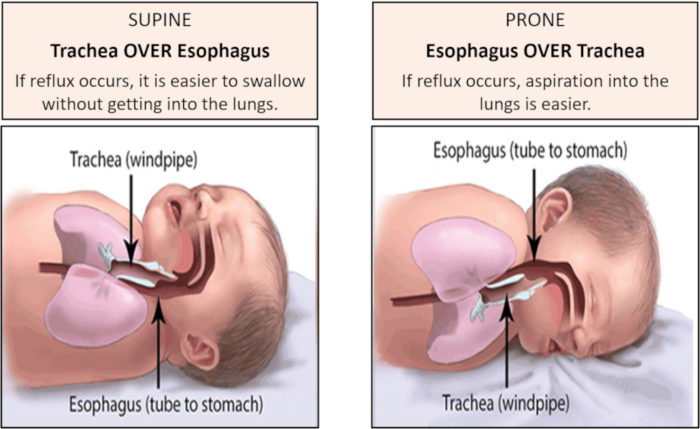

Supine versus Prone position

– In the supine position: upper airway is above the esophagus, allowing any regurgitated milk to be swallowed.

– In the prone position: esophagus is above the upper airway, so aspiration is possible.

– In the side position, the infant is at risk to roll onto the prone position.

Safe Sleep Recommendations

- Position baby on their back (supine), not on their side or tummy (prone), starting at birth or within a few hours.

- Rotate baby’s head side-to-side while supine, and rotate baby’s position in the crib.

- Continue positioning up to age 1 year, even after baby self-positions.

- Room share, do not bed-share; bed-sharing increases the risk of sleep-related deaths, including SIDS.

Sleep positioning devices

Since 2010, no sleep positioning devices are approved by the FDA or AAP; this includes sleep positioners, wedges, nests, anti-roll products, neck rolls, inclined sleepers, travel and compact bassinets, in-bed sleepers, nursing pillows, hammocks, etc. Beware of medical claims about sleep positioners, only federally regulated, safety-tested infant sleep products (cribs, bassinets/cradles, play yards, and bedside sleepers) should be trusted.

Swaddling recommendations

Swaddling has many more disadvantages than advantages.

- When done correctly, swaddling can be an effective technique to help calm very young infants and decrease physiologic distress (crying, pain, feeling cold).

- Increased risk of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome). Swaddling may decrease a baby’s arousal so it’s harder for the baby to wake up; decreased arousal may be a reason that babies die of SIDS.

- Increased risk for overheating and hyperthermia.

- Increased risk of accidental suffocation, if babies are placed on their stomach, or on their side then roll onto their stomach.

- Increased risk for respiratory infections, when swaddles are too tight and restrict chest movement.

- Increased risk for hip dislocation or dysplasia, when swaddles are too tight across hips and legs.

- Decreases normal newborn movement, which increases risk for plagiocephaly.

References

Infographic Symmetry Quick Screen for head/face/neck asymmetry: Symmetry Quick Screen

AAP comprehensive health screening recommendations: AAP Periodicity Schedule 2022

Plagiocephaly

AAP. Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP; April 2022.

AAP. Persing J, James H, Swanson J, Kattwinkel J. AAP Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Plastic Surgery, Section on Neurological Surgery. Prevention and management of positional skull deformities in infants. Pediatrics. 2003;112:199-202.

AAP. Laughlin J, Luerssen TG, Dias MS. AAP Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Neurological Surgery. Prevention and management of positional skull deformities in infants. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1236-1241.

Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), Section on Pediatric Neurosurgery. Guidelines for the management of patients with positional plagiocephaly. Neurosurg. Nov 2016.

American Nurses Association (ANA). Steinmann LC. Newborn positioning, plagiocephaly screening and parent education. Am Nurse Today. Feb 2016;11(2).

Steinberg JP, Rawlani R, Humphries LS, Rawlani V, Vicari FA. Effectiveness of conservative therapy and helmet therapy for positional cranial deformation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(3):833.

Seruya M, Oh AK, Taylor JH, Sauerhammer TM, Rogers GF. Helmet treatment of deformational plagiocephaly: The relationship between age at initiation and rate of correction. Plast Reconstr Surg. Jan 2013;131(1):55e-61e.

Kaplan SL, Coulter CP, Fetters L. Physical therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2013;25:348-394.

Looman WS, Flannery AB. Evidence-based care of the child with deformational plagiocephaly, Part I: Assessment and diagnosis. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26:242-50.

Graham JM, Kreutzman J, Earl D, Halberg A, Samayoa C, Guo X. Deformational brachycephaly in supine-sleeping infants. J Pediatr. 2005;146:253.

Ridgway EB, Weiner HL. Skull deformities. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:359-387.

Safe Sleep

AAP. The AAP Parenting Website. https://www.healthychildren.org

AAP. Moon RY, Carlin RF, Hand I. AAP Policy Statement June 21.2022. AAP Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and the Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Sleep-related infant deaths: Updates 2022 recommendations for reducing infant deaths in the sleep environment. Pediatrics. 2022;150(1):28.

AAP. How to Keep Your Sleeping Baby Safe: AAP Policy Explained. July 2022. https://healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/sleep/Pages/a-parents-guide-to-safe-sleep.aspx

AAP. Moon RY, Hauck FR, Colson ER. Safe infant sleep interventions: What is the evidence for successful behavior change? Curr Pediatr Rev. Feb 2016;12(1):67–75.

Safe To Sleep.® U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://safetosleep.nichd.nih.gov/

FDA. Baby Products with SIDS Prevention Claims. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/products-and-medical-procedures/baby-products-sids-prevention-claims

Swaddling

AAP. Swaddling: Is it Safe? July 2022. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/diapers-clothing/Pages/Swaddling-Is-it-Safe.aspx

International Hip Dysplasia Institute. Hip Healthy Swaddling. https://hipdysplasia.org/can-promote-hip-healthy-swaddling/